Missing Negros in the Time of the Monster's War — 12.10.2020

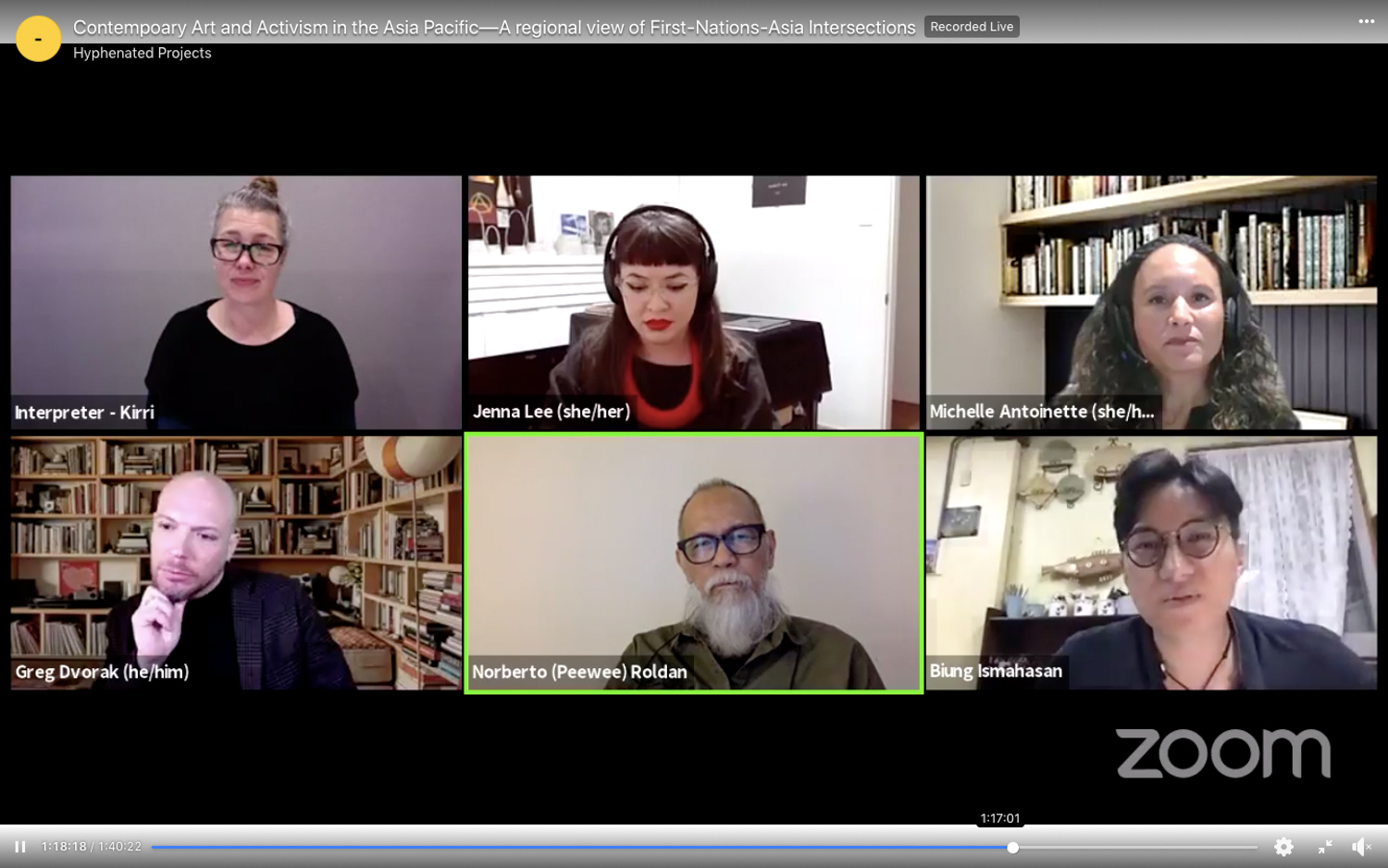

The text below was presented by Norberto Roldan during “Contemporary Art and Activism in the Asia Pacific — A Regional View of First Nations-Asia Intersections” presented by Hyphenated Projects and Incinerator Gallery on December 9, 2020 as part of Hyphenated Biennial (Melbourne). Other guests include Jenna Lee, Biung Ismahasan, Greg Dvorak, and Michelle Antoinette (moderator).

BACOLOD

In 1980, under Ferdinand Marcos’ Martial Law, I moved from Manila to Bacolod City, the capital of Negros Occidental.

During a very turbulent period in our country’s political history, I decided to manage a sugar farm. I never imagined myself becoming a political activist, but having been exposed to the realities of a semi-feudal system prevailing in this sugar-producing province easily turned me into one. As a reluctant “sugar planter,” I was exposed to the “hacienda” life, a capital-intensive plantation system devoted solely to sugar cultivation. Hence, by its very nature as a monocrop economy, the farming system was never designed to be self-sufficient. I have witnessed how sugar workers had been exploited through unfair labor practices.

During this period, as the island was struggling with social unrest, the political upheaval against Ferdinand Marcos was gaining momentum nationwide. The insurgency being waged by the Communist Party of the Philippines and the New People’s Army was at its peak. A revolution was unfolding in the countryside with many remote villages in Negros declared by the revolutionary movement as liberated zones. This was a particular period in our history when one was expected to take sides.

In 1983, following the assassination of opposition leader Benigno Aquino, the Concerned Artists of the Philippines (CAP) was organized in Manila and, shortly after, a chapter was formed in Bacolod. It became the umbrella organization of cultural workers and progressive artists working in theater, music, literature, and visual arts. CAP was at the forefront of protest actions in the province, leading a cultural movement not only against the Marcos dictatorship but also against a semi-feudal system that has persistently oppressed and exploited sugar workers for several generations. I became the vice chair of the CAP in Negros and that was how I became a cultural worker and an activist.

As members of a progressive organization identified with the Left, our activities were always under government scrutiny. Our task was to produce banners, murals, and literature for rallies and mass actions and we operated under constant threat of military harassment and detention. Under the dictatorship, activists, cultural workers, artists, journalists, academics, and intellectuals who were sympathetic to the plight of the poor and the oppressed were marked as enemies of the State. During the Marcos regime, thousands of these perceived enemies were either imprisoned, tortured, raped, or killed.

After the EDSA Revolution in 1986 which saw the exile of Marcos and the installation of Corazon Aquino as president of the Philippines, the CAP in Negros started to fall apart. Many artists believed in the democratic space promised by the Aquino presidency and thus decided to move towards less radical engagements. Members saw this as an opportunity to distance from CAP and to shed off a political stigma — that of being branded as mere propagandists of the Left — and pursue a practice in more legitimate institutional venues.

To keep the alliance intact with those who decided to leave CAP, I founded Black Artists of Asia (BAA) with comrades who were still committed to pursue art as a tool to bring about social change but outside the organizational influence of the national democratic movement. After putting in place a structure to hold BAA together, I then left the country for a two-year self-imposed exile and stayed in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia between 1987 and 1989.

SYDNEY

The initial activities of BAA centered on exhibitions aimed at bringing the real stories of the sugar workers in Negros to the attention of the world. Early on, BAA had sent exhibitions to Rotterdam in 1986 and to Tokyo in 1987, both facilitated by the Philippine international solidarity movement in the Netherlands and Japan. But, by far, the most ambitious project BAA has ever organized was the exhibition series “Images of the Continuing Struggle” in 1989 in Sydney. The main section of the exhibition was held at Artspace, the prints and photography section was held at Firstdraft, and some selected works were hung in La Lucha Continua (1989), a festival of progressive theater and films from third world countries, in Belvoir Street Theatre.

In the Sunday Art Section of The Sydney Morning Herald on March 4, 1989, Christopher Allen wrote:

“The Filipino work at Artspace takes us far from the international contemporary art world and into one of those cultures of our region which are at once so familiar and so foreign to us. Of all the ASEAN nations, the Philippines have had the most extreme experience of colonialism. Four centuries of Spanish and, more recently, American rule have left the country Catholic and largely English-speaking. To a visitor passing through Manila, the country seems to exist in a cultural limbo between East and West. Politically, it represents an often brave attempt to run an American-style democracy on an unstable foundation of poverty, corruption, and gangsterism. The most hopeful sign that one finds as a casual visitor is a genuinely free and energetically critical press, perhaps unique among our neighbours in the region.

The art in this exhibition is also politically critical, coming from a group of artists in the central-southern island of Negros. And this is an art determined overwhelmingly by extrinsic factors — by part it is designed to play in a political struggle…”

Christopher Allen may as well have spoken about the present when he said, “Politically, [the Philippines] represents an often brave attempt to run an American-style democracy on an unstable foundation of poverty, corruption and gangsterism.” But the “genuinely free and energetically critical press” is no longer true. Duterte and his allies in Congress shut down the biggest broadcasting network in the Philippines last September and they continue to harass and intimidate the press that are critical of the administration.

BACK TO BACOLOD

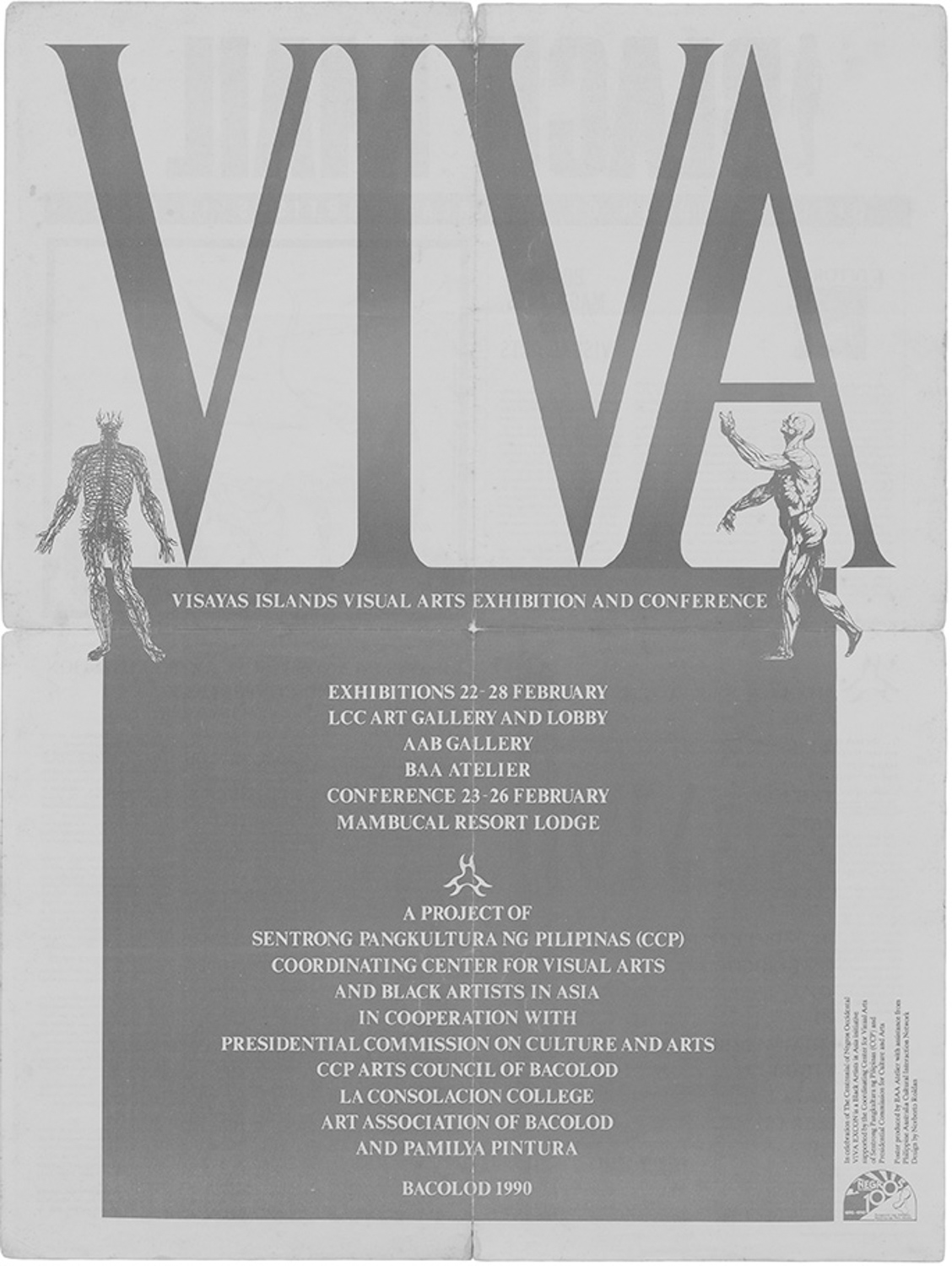

I returned to the Philippines in late 1989 and, together with BAA, set into motion the launching of the first Visayas Islands Visual Arts Exhibition and Conference, or VIVA ExCon. The first VIVA ExCon was held in Bacolod in 1990. It was an attempt to bridge the islands by linking up art communities, to provide a venue for sharing knowledge, to discuss issues affecting the region, and to consolidate the Visayan art scene. It was created to address the specific urgencies of Visayan artists and cultural workers persisting in the shadows of Manila’s cultural imperialism.

During VIVA ExCon 2018, when I took up again the role of artistic director, VIVA ExCon asserted its basic role as a platform for political discourse and actions concerning the rural areas.

Much has been said about the success of VIVA ExCon as the longest-running, artist-led biennial in the country. Its modest claim of having “bridged” the islands in the Visayas has, over the years, been repeatedly affirmed. But as an artists’ initiative, it still has a long way to go as far as its social aspirations of contributing and uplifting the lives of people in the countryside.

The rural ecology has been rapidly changing. Prospects in agriculture and aquaculture are met with daunting challenges not only in the Visayas but throughout the rest of the Philippines. Unstable policies on land conversion from agricultural to industrial zones, sketchy implementation of real land reform, damages to agricultural crops due to natural calamities, and most of all, the ongoing killings of farmers, activists, and human rights advocates and the ongoing militarization of the countrysides are just the most formidable obstacles for the rural sector to develop into peaceful and more productive communities.

After 30 years since it started in Bacolod, the real work of VIVA ExCon has barely begun.

The CAP in Manila has taken up its role again as a leading force in the protest movement. In the urban centers, Respond and Break the Silence Against the Killings (RESBAK) has been actively involved in resisting extrajudicial killings brought about by Duterte’s drug war, while the Artist Alliance for Genuine Land Reform and Rural Development (SAKA) has allied with and is working closely with the peasant movement in facing the challenges of rural democratization in the Philippines.

On the other hand, with the underground movement and the New People’s Army gaining strength again in the rural areas, the Philippines is back to where it was in the ‘80s, perhaps in an even worse situation.

Norberto Roldan

December 10, 2020

More info:

Contemporary Art and Activism in the Asia Pacific — A Regional View of First Nations-Asia Intersections

https://fb.watch/2hq5UT75Gx/

VIVA EXCON 2020

https://www.facebook.com/vivaexcon2020

Mural for a rally painted by CAP-Negros artists, 1986. Image from Green Papaya Art Projects Archives.

Public mural painted by Visayan artists and organized by CAP-Negros, 1987. Image from Green Papaya Art Projects Archives.

Poster for a concert organized by CAP-Negros, illustration by Charlie Co, design by Norberto Roldan, 1986. Image from Green Papaya Art Projects Archives.

Poster for a festival of people’s culture, illustration and design by Nunelucio Alvarado, 1984. Image from Green Papaya Art Projects Archives.

Poster for BAA exhibition in Japan, design by Norberto Roldan, 1987. Image from Green Papaya Art Projects Archives.

Poster for BAA exhibition in Bacolod, design by Norberto Roldan, 1988. Image from Green Papaya Art Projects Archives.

Flyer for a BAA exhibition in Artspace, Sydney, design by Norberto Roldan, 1989. Image from Green Papaya Art Projects Archives.

Flyer for a BAA exhibition in Firstdraft, Sydney, design by Norberto Roldan, 1989. Image from Green Papaya Art Projects Archives.

Poster for the first VIVA ExCon in Bacolod, design by Norberto Roldan, 1990. Image from Green Papaya Art Projects Archives.